Lost Under the Glass: Walking Between Two 19th-Century Passages from Valencia to Istanbul

Lost Under the Glass

On the Threshold of the 19th Century, Walking Between Two Passages from Valencia to Beyoğlu

🎧 Juan Arenosa – Cordelia (2024) A mute, timeless, spaceless accompaniment between Valencia and Istanbul.

Going through a passage is often not just getting from one street to another. When stepping under the glass, the sound changes, the light softens, and the gait slows down on its own.

This is how I feel when I walk under the glass cover of Pasaje Ripalda in Valencia; Also in the Flower Passage in Istanbul. Despite their differences, both seem to be the product of the desire to make modern life visible and experiential through architecture in the last quarter of the 19th century; Like two different sentences from the same period, written in glass and stone.

The end of the 19th century marks a period in which daily life in European and Mediterranean cities began to overflow into the public sphere. Industrialization, new transportation networks and the growing bourgeois class lead to the emergence of new spaces suitable for wandering, looking and appearing in urban centers. Arcades are the architectural equivalent of this need: intermediate spaces located between the street and the interior, softening the boundaries of the public and the private. Walter Benjamin's treatment of passages as a lens through which to read the everyday life of modernity is therefore significant; The passage is a stage where modernity is not only represented but experienced in person.

At the end of the 19th century, Valencia was a relatively stable bourgeois city, strengthened by Mediterranean trade. Cafes, clubs, and arcades become essential scenes of public life, especially for the middle and upper classes. Walking around the city center, looking at the shop windows and being visible in a controlled manner are considered part of modern life. Buildings such as Ripalda Passage are the spatial equivalent of this orderly and measured social life; There is a crowd but it does not disperse, public life flows within certain limits.

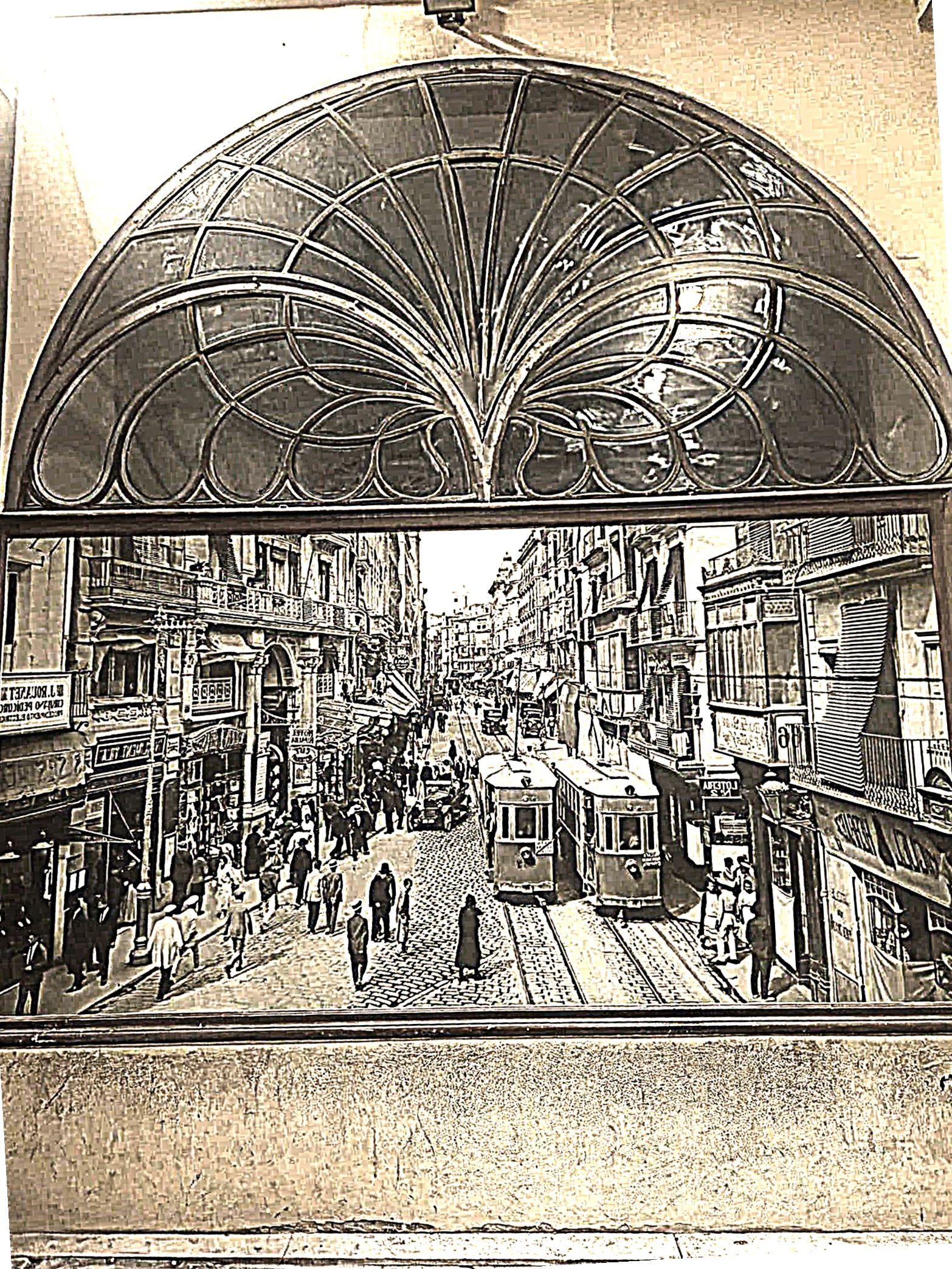

In the same period, Istanbul had a much more fragmented and active social fabric. The Beyoglu line, in particular, is one of the most cosmopolitan areas of the Ottoman capital: theaters, taverns, cafes, hotels and embassies are located next to each other. Different languages, classes and cultures merge in everyday life. Public life is noisier, more unexpected and more porous. Structures like the Cité de Péra are not merely a space for circulation within this intense social contact, but work as a natural extension of encounters and pauses.

Today, the experience in these two passages differs markedly. Walking through Ripalda Passage is still orderly and calm; The space makes the user feel clearly where to enter and where to exit. The transition is fluid, the sense of direction is clear, and the walk is uninterrupted. In Çiçek Pasajı, the march is often interrupted by today's crowd; the light scatters, the sounds overlap, the people stop and linger. For this reason, moving from one place to another is often intertwined with staying.

Ripalda Passage Valencia Spain

pasaje ripalda valencia espana

Flower Passage Istanbul Turkiye

cite de pera istanbul turkiye

Where does this difference come from?

This difference must be due to the fact that these two buildings, which were designed in a similar architectural order in the past, are lived in different ways with the daily rhythm of cities today. The reason why Ripalda Passage is still predominantly used as a passing place is that the building has been designed to encourage a regular circulation from the beginning. Designed by architect Joaquín María Arnau Miramón in 1889, the passage was built in the historic center of Valencia on the initiative of the Ripalda family, one of the wealthy families of the period. The same family built a residential building in Miramón along with the passage, representing both the public and private faces of modern life with architecture.

Inspired by 19th-century arcades in Italy and France, this arrangement offers a conscious break from the hustle and bustle of urban streets; It emphasizes progress rather than stopping, transition rather than stalling. For this reason, Ripalda works as an inner street that prioritizes walking from the day it was first designed.

Cité de Péra and Another Rhythm of Beyoğlu

Cité de Péra, the predecessor of the Flower Passage, is nourished by the same ideal of modernity as the idea of the passage that emerged in 19th century Europe, but it is not an exact copy of this typology. Like many arcades in Europe, it offers a glass-covered interior and a commercial circulation area; However, the transition is part of a mixed-use structure rather than the primary function of the building. The fact that there are residences on the upper floors and shops on the lower floors makes this place not just a passage to be crossed, but a living structure.

This situation is closely related to the context of Beyoğlu, where the building is located. In late 19th century Istanbul, Beyoğlu was the center of a multilingual and multicultural social life, where theaters, cafes, hotels and diplomatic missions were concentrated. The Cité de Péra takes shape as a permeable space within this vibrant environment, open to everyday encounters from the outset.

From this point of view, Ripalda offers an example closer to the classical passage logic; Cité de Péra presents a more reciprocal interpretation of the idea of the passage, adapted to the social and spatial conditions of Beyoğlu. Today, the difference in usage between the two passages can be easily understood when viewed through this distinction.

Ripalda passage valencia

earliest passageway in Valencia Spain

Flower Passage Istanbul Turkiye

Cite de Pera Istanbul Turkiye

Pasaje Ripalda

Ripalda Passage Valencia Espania

A Walk Under the Glass

Perhaps the next thing to do is to see fewer places and walk a little slower on your next

visit to Istanbul. To turn into the crowd of Istiklal and pass through the Flower Passage without rushing; Listening to the tempo of the crowd here, remembering that measured rhythm felt under the glass cover of Ripalda in Valencia. Noticing the light filtering through the glass, the sounds stuck between the tables, and the lives touching each other.

There is still an invisible link between the steps taken in Valencia on the threshold of the 19th century and those in Istanbul. It is not necessary to know history to feel that connection; Sometimes it is enough to just keep walking. Don't shorten your route on your next hike.

If you like surprises like Istanbul, take the risk of lingering in a passage for a while.